Private equity firms typically use leverage (debt) to increase the return on the firm's invested capital. The amount of leverage employed is normally determined by the target's ability to service debt with cash, generated through operations. The ability to generate cash allows the private equity investor to contribute more debt to the transaction. Because of the aggressive use of leverage, often, the cash flow a business generates in the early years following the acquisition is almost entirely consumed by the debt service. Furthermore, if the strategy is to grow business, and it usually is, growth also consumes cash. For this reason, private equity investors are keenly focused on the cash flow of the business.

Capital Structure is defined as the way a company finances itself through the combination of equities or borrowings. This structure varies greatly from one company to another. One may choose financing itself mainly by shareholder funding, whereas another company may prefer borrowings. In either case, companies try to maximise their market value.

The financing mix that minimises the overall cost of finance and maximises market value is defined as the optimal capital structure. Determination of optimal capital structure has been one of the main topics for theoreticians and financial managers. Here are some prevailing theories and their discussions regarding private equity contribution on capital structure.

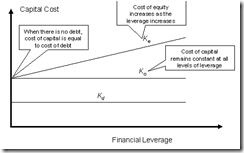

This approach states that the proportion of debt and equity in the firm’s structure does not have any impact on the firm’s value or its cost of capital. The NOI approach assumes that while the cost of debt is constant for all levels of leverage, the cost of equity increases linearly as leverage increases. This increase is explained by the increase in the financial risk to the firm as it increases the proportion of debt in its capital structure. Cost of equity increases because the shareholders expect a higher rate of return to cover the risk.

Therefore NOI approach concludes that there cannot be any optimum capital structure for a firm.

According to this approach:

- The overall capitalisation rate remains constant for all levels of financial leverage

- The cost of debt also remains constant for all levels of financial leverage

- The cost of equity increases linearly with financial leverage

Following graph shows how costs vary with leverage.

Ko: average cost of capital

Kd: cost of debt

Ke: cost of equity

Figure 1. Capital cost according to NOI approach

If what is argued in this approach was to be completely applicable to the real practices of private equity firms, the attempt of increasing leverage would be meaningless. However there is one important point made clear with this approach is that the profit expectation of investors are getting higher with increased leverage. This is usually correct for common shareholders in listed companies. But as the private equity investors increase leverage, public equity contribution is getting less in the total capital and public equity investors’ concerns and their valuation is getting less important too. Therefore, even in the theoretical level, the assumption that capital cost remains constant even at higher leverage does not hold for this case.

In 1958 Modigliani and Miller (M&M) presented their ground breaking study and changed all the perception of financial managers who are trying to maximise their companies’ value. They advocated that the relationship between financial leverage and the cost of capital is explained by the NOI approach and provide behavioural justification for a constant Ko over the entire range of financial leverage possibilities.

They argued they the value of the company is irrelevant of how its capital is financed through the combination of debt and equity. This argument was suggested under the assumption of a market where there is no corporate taxation. If a company is not liable to pay taxes, the value that it can generate trough equity is supposed to be the same as the value generated through debt. In other words, companies can use leverage as much as they want as it has no effect on company value.

However, it is obvious that taxes form important part of the liabilities that managers have to take into account. And in fact it is one of the most important parameter that affects the capital structure. Even if M&M’s contribution of irrelevance theory, financial managers’ main aim is still to maximize company value and minimize the cost of capital.

The biggest advantage of debt over equity is that taxes are paid after interest. A manager would prefer to pay interest for their capital funding rather than paying a tax which costs more. So, the leverage would be pushed as much as possible until the point that it starts posing a danger of risk for business. As the leverage is increased, lenders would be less willing to give loan and investors would be less likely to invest so both cost of debt and cost of equity will rise. Therefore the most efficient capital structure must be sought where cost of capital is minimum.

According to M&M it is pointless to try to find the minimum cost of capital; financial managers may change the level of leverage as they wanted. So there is no way for any kind of capital structure inefficiencies by the private equity firm’s leverage adjustments. In fact, financial managers may use the same level of leverage even without using private equity and have the same chance to increase the cash flow as a private equity firm would do. However it is not the case in the real world and there are loads of other concerns which need attention by financial managers to keep the leverage in industry levels.

The next approach is more successful at explaining managers’ attitudes against determining leverage levels.

And also sheds more light on why leverage level would significantly differ in a company when its stakes are bought by a private equity fund management firms.

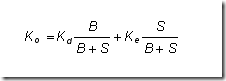

According to this approach, the cost of debt and the cost of equity do not change with a change in the leverage ratio, which results in a decline in cost of capital as leverage increases. This can be explained by the following equation which is used for calculation of weighted average of cost of capital.

- Ko: average cost of capital

- Kd: cost of debt

- Ke: cost of equity

- B: market value of debt

- S: market value of equity

Figure 2. Capital cost according to NI approach

Since cost of debt is less than cost of equity and cost of debt gets higher weight against cost of equity as leverage increases; the average cost of capital decreases with the leverage. Figure 2 is the illustration of how weighted average of cost of capital changes with the leverage level.

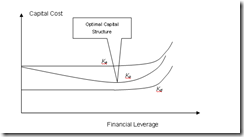

Traditional approach is midway between the NI and the NOI approach. The main propositions of this approach are:

- The cost of debt remains almost constant up to a certain degree of leverage but rises thereafter at an increasing rate.

- The cost of equity remains more or less constant or rises gradually up to a certain degree of leverage and rises sharply thereafter.

The cost of capital due to the behaviour of the cost of debt and cost of equity

- Decreases up to a certain point

- Remains more or less constant for moderate increases in leverage thereafter

- Rises beyond that level at an increasing rate.

Figure 3. Capital cost according to traditional approach

As depicted in Figure 3, low-cost debt is not rising initially and replaces more expensive equity financing and Ko declines. Then, increasing financial leverage and the associated increase in Ke offsets the benefits of lower cost debt financing. Therefore according to this approach, cost of capital may hit a lowest point at a certain leverage level, where financial managers are trying to find. This is also the point where the firm’s total value will be the largest.

In a public company, finding optimum capital structure may be the one of the main aims for a financial manager. And the proposed theory presented above is closest to what is happening in practice. However when a public company chooses private equity to achieve its long term goals, the aim which is sought to maximise company value rather changes to realize potential growth, generate cash flow and satisfy private equity investors’ expectations.

or

or  .

.